International Institute for Environment and Development

80-86 Gray's Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH

info@iied.org

www.iied.org

tel: +44 (0)20 3463 7399

fax: +44 (0)20 3514 9055

Case Studies:

Rehabilitation of forest in Rivas, Nicaragua

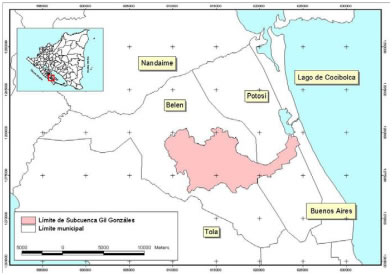

Public-private alliance between the municipality and the sugar industry, which, supported by international cooperation, created a fund to finance reforestation and protection of forests in the upper basin. Figure: Location of scheme (Flores-Barboza et al., 2011)

Ongoing since 2007 – active as of 2011.

The initiative is promoted by the local municipality (Alcaldia de Belén), and emerges as part of a pilot scheme in the land management and development in the Belen Municipality. The municipality looked for support with other projects in the vicinity, specifically Proyecto Suroeste (Rural Development Institute (IDR)/ German Technical Cooperation -Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). GTZ has been key in supporting the development plan.

SupplyThe objective of the scheme is to target two micro-watersheds: Gil-Gonzalez and Las Lajas. However, in a first phase efforts were focused in Gil Gonzalez. The scheme targets farmers living in water recharge priority areas. Target area originally 104 hectares but now increased to 512 hectares. By 2011 there were a total of 98 contracts signed, benefiting 93 farmers. DemandLed by international organizations (GTZ in particular), the scheme tried hard to engage Compañía Azucarera del Sur (CASUR),a sugar mill, which was obtained after lengthy negotiations. CASUR faces nearly 45 per cent of the scheme costs and carries other responsibilities (e.g. administering operational costs and project management among others) (Baltonado n.d.; INAFOR & FAO, 2010). The donors will not support the scheme indefinitely, so new buyers must be continuously pursued. Prospective buyers are agriculture producers (banana and rice producers) (Baltonado n.d.; INAFOR & FAO, 2010) (see Perez, 2011). IntermediaryUnclear. FacilitatorGerman cooperation agencies (the German Development Service (DED) and GTZ) support and promote the initiative. They carry several tasks (e.g. monitoring and scheme promotion among others) and have borne nearly 50 per cent of the scheme costs which allowed the scheme implementation despite the high transaction costs found at its infancy (Nicaraguan National Forestry Institute (INAFOR in Spanish) & FAO 2010; Baltonado n.d.). GTZ and DED have played the role of facilitators in this case (Baltonado n.d.) [see Pérez ]).

ServiceWater quality and quantity. Commodity

Payment MechanismIn-kind (seedlings, tools, technical assistance). Cash, ongoing: C$713 per hectare per year. Terms of PaymentParticipants receive one-off ‘stock’ payment (wire, machetes, and other tools) for management activities. Four fire brigades were also equipped. Seedlings are also given free for reforestation. Funds Involved

Analysis of costs and benefits EconomicThe first stage of the project involved the purchase of 70,000 seedlings from communal greenhouses, with rather limited success as plants were maltreated during transport, and the lack of control and soil preparation for the planting of seedlings. The communal aspect of the greenhouses were not all successful either, as not all farmers contributed equal amounts of work. A new approach introduced in 2009 involved family greenhouses, helping to establish 300 plants in participants’ farms, with better success rates.

EnvironmentalFrom Perez (2011): Some analysis of water quality and quantity has been done in the micro-watershed (CIRA/UNAN, Alcaldía de Belén & Proyecto Sur Oeste, 2007). According to Somarriba (2011), "an institute have looked at measures that have to be taken to overcome the pressures." She added, "However, data gathered is not enough and a biophysical study that determines whether the area tackled is indeed the key one for water recharge was not implemented due the high cost that it entails ($70,000). This money is not available" (Somarriba 2011). For the previous reasons, there is some uncertainty regarding the scheme impacts over Watershed Services (WS) (Somarriba 2011).

According to Somarriba (2011), a decline in the deforestation rate, and in the use of agrichemicals has been observed, and the water level has increased from the time the scheme began (Somarriba 2011). However, no hard-evidence was obtained while writing this review to back up those statements.

Problems affecting effectiveness of the project include:

SocialNinety-three families benefitted, of which 20 are headed by women. Capacity building for "environmental promoters," of which 35 are women and 80 per cent young people.

In Nicaragua there is no law directly dealing with Environmental Services (ES), or payments, until now. Current experiences of Payment for Environmental Services (PES) in Nicaragua have been built around other legislative forms:

Monitoring is done by GTZ. It focuses on contract compliance and annual monitoring of water quality and quantity. So far actual monitoring of water quality/quantity has not been possible because of cost (Flores, 2011).

Between 2008 and 2009 the main constraints of the project were: a) legal situation of farm tenure, which limited participation until it was agreed that possession rights were enough; b) some costs were not initially budgeted (i.e. GIS), underestimated, or time-lags were not considered (i.e. time required for regeneration); c) lack of participation from all members of the project, which resulted in work overloads and delays for a few; d) some of the promised funding were not fulfilled; e) management delays (Flores, 2011).

The negotiation process has been slow, as there are some constraints, which are mainly poorness and lack of sellers’ ownership over land. Additionally, the scheme failed to identify important costs in the initial phases. Although there is not recognition of PES by the national government, it did not constrain the scheme implementation (Baltonado n.d.). Despite these problems, it seems that there is willingness to continue with the scheme from the different stakeholders (Baltonado n.d.; INAFOR & FAO, 2010) (In Perez, 2011).

Personal interview with Ms. Somarriba, scheme facilitator, by Martin Perez (Perez-Alvarez 2011) for his dissertation.

|

|

© 2012 International Institute for Environment and Development . All rights reserved.