Costa Rica- National Payment for Environmental Services (PES) programme

Costa Rica's PES Programme- "a financial mechanism for the recuperation and conservation of forest cover in Costa Rica"

Summary

The government-led Costa Rican PES Programme rewards forest owners for four bundled Environmental Services (ES) (watershed protection, carbon sequestration, landscape beauty and biodiversity protection) their forests provide. While the scheme relies heavily on state funds derived from a fuel tax, it has evolved significantly and keeps trying new ways to further engage the private sector (mostly Hydroelectric Power (HEP) producers). Fondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal (FONAFIFO) and local NGOs like FUNDECOR, play important intermediary roles.

Maturity of the initiative

Ongoing since 1997, active in 2011.

Driver

A combination of political leadership and the continuous evolution of forestry sector laws since the 1960s (forest cover decreased from 72 per cent in 1950 to 26 per cent in 1983; by 2002, it had recovered to 45 per cent). During the mid-1990s Costa Rica, faced with the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the World Bank, was forced to withdraw the generous subsidies it had offered landowners for reforestation. This led the forestry lobby to search for other financing means, which in turn prompted the strong environmental movement (still fresh after Rio) to try to reshape forestry tactics. Political support was ready in the form of Rene Castro of the Ministry of Environment (MINAE) , the president of Costa Rica, Jose Figueres and a team of key environmental advisors. The PES programme was launched in 1996 with the creation of a law for ES and a government commitment to dedicate five per cent of the Fuel Tax to this end. It began operations in 1997.

The proposal for the revised Forestry Law that underpins the PES scheme was the result of dedication and particular support from the then Minister for the Environment, who assessed the feasibility of the scheme as his PhD thesis. The draft of the strategy was widely circulated for comments (conservation groups had the chance to contribute) and after five years, during which criticisms and opposition were addressed, it was finally approved. Socio-economic changes also supported the implementation of the new legislation (e.g.fall in the price of meat, increase in tourism, general changes in the active structure of the population that was becoming more urban).

Stakeholders

Supply

Private landowners. Although initially the PES was seen as a way to provide additional resources for the national park system, the focus quickly shifted to private lands. Landowners apply for the programme on a first-come-first-served basis, although this is changing and now strategic areas are being created to support the creation of biological corridors, protection of strategic water catchments or to take into account areas with high poverty levels (see under Commodity for levels of payments).

The activities promoted under PES are forest conservation (priority areas and areas for protection of water resources) and forest plantations (commercial species or native species in natural regeneration areas). A more recent category is agroforestry, where landowners receive payments depending on the number of trees they plant as part of agroforestry systems (e.g. wind barriers, live hedges, shade, etc). The programme initially included sustainable forest management but this category was later eliminated on the grounds that the landowner would have sufficient returns from the timber extracted. However, farmers promoting sustainable forest management have access to payments for conservation for those areas that need to be left intact. A new natural regeneration modality "Kyoto lands" is to begin in 2006 (see Commodity for more details).

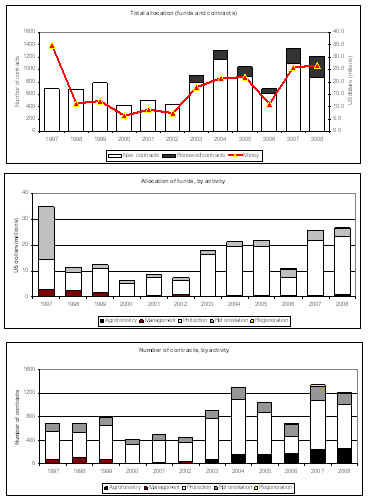

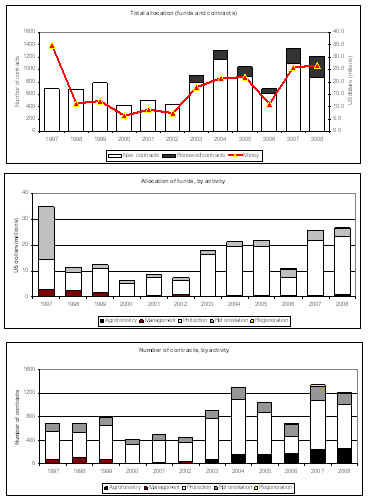

The figures in the table below show the number of contracts issued and the area corresponding to them since the beginning of the scheme. As contracts last for five years, and could be renewed after that, the total area contracted since 1997 exceeds the area currently enrolled in the scheme (for example, contracts that began in 1997 could have been renewed in 2003). By October 2005, the programme had approximately 250,000 hectares under contract of which 95 per cent was for conservation, four per cent for reforestation and one per cent for the now discontinued modality of sustainable forest management (Global Environment Facility (GEF), 2005).

Figure: distribution of contracts, by year and activity (Porras, 2010).

Priority criteria vary according to the type of project. All these priorities are overlaid on a Geographical Information System (GIS) database which allows FONAFIFO to identify areas of highest priority. Within those priority areas, in-coming applications are dealt with on a first-come-first-served basis.

A) Projects for Protection:

- areas located in biological corridors (Sistema Nacional de Areas de Conservacion [SINAC]) especially those considered of high priority by the ecomarkets project (GEF);

- areas within the influence area of the Huetar Norte Forestry project (KfW);

- renovation of previously existing contracts, as long as they are located within the above mentioned priority areas;

- forest areas located in strategic areas for the protection of water resources of interest for rural aqueducts, national or municipal utilities;

- privately owned areas, within the protected areas, that have not been acquired or expropriated by the State;

- Projects located in areas where the Social Development Index (SDI) is under 40 per cent. The SDI is a relative index combining educational, health indicators with social indicators such as number of single mother births and electricity consumption, where zero per cent is the poorest area and 100 per cent the best in Costa Rica (Ortiz et al., 2003).

B) Reforestation projects:

- Land-use aptitude for forest plantations;

- Location in relation to:

i) Conservation district in which the project is located; however, in the case of reforestation with native or endangered species, or natural regeneration, this does not apply, as the entire country is prioritised;

ii) donor target areas (KfW);

- renovation of previously existing contracts;

- Projects located in areas where the SDI is under 40 per cent .

C) Agroforestry

- Projects submitted by organizations or individuals with certified capacity in managing forest/timber trees in agroforestry regimes;

- land-use aptitude for forestry;

- areas of high risk of soil or water degradation and biodiversity loss.

D) Natural generation (beginning in 2006) in "Kyoto lands" - areas that were deforested before 1986 and that can now be left for natural regeneration: payment is US$41 per hectare per year over five years.

Rules on size of projects:

i) Reforestation: single applications: 1-300 hectares per year; group applications: up to 50 hectares per year for each of the landowners;

ii) conservation 2-300 hectares;

iii) in indigenous reserves: maximum area is 600 hectares, per PES modality, each year;

iv) agroforestry: 350 to 3,500 trees per landowner, with limited densities according to the type/use of the trees.

However, for each of the three project types, properties usually have to be over 10 hectares to make it worthwhile to incur the transaction costs involved.

Demand

Pooled demand. Demand for ES comes from several sources. The most important contribution comes from the Fuel Tax, partly justified as the country's investment in carbon sequestration and clean air. Since 2006 a third of the Water Tax (Canon del Agua) are diverted to FONAFIFO to help protect strategic water areas. Other funds come from agreements with pharmaceutical companies interested in bio-prospecting, sale of carbon credits under (and outside) the Kyoto Protocol, grants from international donors such as KfW and GEF, a loan from the World Bank to support market creation (Ecomarkets, which is now in its second phase - approved in 2006 - under a different name: Scaling Up and Mainstreaming Payments for Environmental Services Project P098838], and private agreements with companies in the country for water protection. Some of these include contracts with hydroelectric projects (Energia Global, Platanar, CNFL), a brewery, and the tourism industry.

Intermediary

Government-intermediary at primary level, and NGO-facilitators at secondary level. The National Forestry Fund, FONAFIFO, is the main intermediary of the system, which has 46 staff, eight local offices, each of them with a forest engineer and an assistant. FONAFIFO distributes payments to landowners who agree in exchange to commit their land either to conservation or to reforestation. They cede the rights over the ES to FONAFIFO, which then "sells" these services either to local companies demanding watershed/landscape services, or to the global community interested in carbon sequestration or biodiversity conservation. FONAFIFO is able to sell "pre-packed," fully guaranteed, bundles of services to the buyers. On the supply side, although landowners can apply directly to FONAFIFO, many of them receive assistance from second tier intermediaries.

Facilitators

SINAC, MINAE, universities, and NGOs were all involved or consulted in the design of the programme. Other facilitators, such as FUNDECOR and Forestry Development Commission of San Carlos (CODEFORSA) provide many ancillary services such as technical capacity. All payments are made and managed through banks and trust funds.

By law, forest engineers (regentes forestales) and forestry organisations act as intermediaries or facilitators. Those local facilitators working with FONAFIFO must comply with some criteria, including: signing an agreement of collaboration; they have to keep a separate bank account to deal with the payments; pre-qualify applicants for the PES; agree to give payments to landowners within 15 days of FONAFIFO making the funds available; collaborate with FONAFIFO with technical assistance, monitoring, and forestry regency contracts; have a written agreement of how much they charge the landowners for their services (it cannot exceed 18 per cent of the payment); have individual contracts with the landowners; and present bank statements to FONAFIFO twice a year showing payments received and made.

The tasks of these facilitators vary. For example: a) grouping smallholders under one umbrella to reduce transaction costs, b) approaching large landowners who are not interested in the paperwork involved, c) helping landowners overcome the bureaucracy of the process. In all the cases, the intermediary supports the landowner and, in exchange for a fee (usually 12-18 per cent of the payment, but no more than that according to FONAFIFO guidelines), assists with technical assistance and monitoring. One example is FUNDECOR, a long-established intermediary, which promotes Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification and works with smallholders.

However, according to FONAFIFO (Alexandra Saenz, June 2005), sometimes intermediaries can actually burden the process and take away too much of the payment that should go to the landowner. Unfortunately, there are no written guidelines to determine the best intermediary and this is a process that must be learnt along the way.

Market design

Service

Bundled: biodiversity protection, watershed protection, carbon sequestration, and landscape beauty. Although for a long time watershed protection implied increases in water flows; this idea is being dropped by FONAFIFO in its new contracts following evidence from hydrological studies that forests are not likely to increase water flows. An extensive consultation about the new Canon del Agua suggests that these funds should not be allocated for reforestation (Tiffer-Sotomayor, 2006).

Commodity

- Conservation and protection of existing ecosystems. Over 80 per cent of payments go towards conservation.

- Reforestation for commercial plantations.

- Improved management practices through agroforestry projects (which may also include shade coffee, afforestation of pasture lands, live hedges providing fodder, or as wind brake barriers). These projects were introduced in 2003 as part of the second generation PES, with the aim of including the ES provided by agricultural activities in the PES compensation scheme. An additional aim was to contribute to rural poverty alleviation by providing an alternative source of income for farmers.

- Rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems for conservation- natural regeneration of the “Kyoto Lands.”

- Sustainable Forest Management (No new contracts since 2002).

Payment mechanism

Over the counter, Intermediary-based, pooled transaction. FONAFIFO collects funds from users (global and local), grants, donations, and loans and pools them into one general fund. Funding is then distributed to private landowners. The initial strategy has been "first come-first served,” although the system is moving slowly towards a more defined strategy of biological corridors and important water-recharge areas. Landowners enter a detailed contract with FONAFIFO, (or local intermediaries) which monitor and (in some cases) provide technical assistance. FONAFIFO has devised a new system, the Certificates for Environmental Services (CES), where the private sector can purchase over the counter, without the substantial paperwork usually involved in previous agreements. Each certificate ensures the protection of one hectare of forest that can be allocated in a place chosen by the buyer, or go towards general protection in other areas (see separate explanation sheet for the Costa Rican CES).

Strength of the provider/user link: weak in most parts, although more local initiatives are being encouraged.

Application procedure and requirements . Priority areas for approving projects are selected every year through a decree.

Landowners who wish to participate in the programme have to provide the following:

a) application form to the regional MINAE office;

b) proof of identity or statutes of an organisation;

c) proof that they hold a legal title to the land. If applicant only holds possession rights then other official requirements are necessary: proof of sale, three independent witnesses, description of the property and its limits, proof that there are no conflicts over the property, etc. All of these have to be publicly authorised by an official lawyer (notario público).

d) proof that they have paid local taxes;

e) an official cadastral map of the property;

f) verification of the size of the area by a professional topographer;

g) (copy of) a cartographic map on a scale of 1:50.000 to indicate location of the area;

h) legal authentication of representative;

i) for sustainable forestry activities, a Forest Management Plan drafted by a professional forestry engineer and approved by the SINAC. Reforestation can only be financed after additional official approval by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Terms of the payment

Cash payments. Payments to landowners made in cash instalments throughout the duration of the contracts. Most contracts are for five years, although in some cases this could vary depending on the preferences of the buyer. For example, contracts where CNFL is the buyer are for 10 years (see separate sheet on CNFL). Buyers of services either make on-going payments throughout the duration of the contracts, or a one-off payment. The choice depends on the firm, and each arrangement has, so far, been negotiated individually. The introduction of the new CES seeks to reduce negotiation time by simply allowing the firms to make one-off payments, valid for five years, and giving them the possibility to renew their certificates at the end of that period.

Although auctions have not yet taken place in Costa Rica, some differentiated payments have taken place, mostly linked to the perception of the environmental service. For example, as part of the latest World Bank financing arrangement of 2006 (Ecomarkets II), land with exceptional environmental service value may receive added compensation.

By 2010 the categories recognised include:

- Reforestation: 1) any species (US$980); 2) native (US$1,470);

- Natural regeneration: 1) in Kyoto Protocol (Clean Development Mechanisms [CDM]) -approved areas (US$320); and elsewhere (US$205);

- Forest protection: 1) general (US$320); 2) inside “paper parks” (US$375), 3) hydrological protection (US$400)

- Forest management (US$250)

- Agroforestry ($US1.30 per tree, and US$1.95 per native tree).

Funds involved

Main source of income is from the Fuel Tax. Significant new sources will arise when the new Water Law (Canon del Agua) is in place, as it introduces mandatory water charges for all users.

Sources of FONAFIFO budget:

- Fuel Tax: (3.5 per cent from every fuel sale) which represents about US$3.5 million per year (2003 figures).

- Water Tax (increased to all water users in 2006, and a third of which goes to FONAFIFO to help protect ES in strategic watersheds).

- Agreements with Public and Private Corporations interested in water ES (aproximately US$560,000 per year)(see individual case-study profiles)

- Hydropower generation (as of 2011, it is unlikely that these contracts have been renewed following the introduction of the Water Tax) :

- Energia Global: US$40, 000 per year

- CNFL: US$436,000 per year

- Platanar: US$39,000 per year

- Bottling company (not renewed after it expired)

- Florida Ice & Farm: US$45,000 per year. The area overlaps with the Empresa de Servicios Públicos de Heredia (ESPH), which contributes with US$22,000 per year for conservation.

- Grants and Loans:

- Ecomarkets II, Mainstreaming Market-Based Instruments for Environmental Management Project. (2006-2012) US$8 million per year.

World Bank loan US$30 million and US$10 million GEF grant to strengthen the existing PES programme and improve participation of smallholders. The project also supports the introduction of the new water tariff and the creation of a biodiversity conservation trust fund, among other objectives.

(previously Ecomercados Project (2000-2005) also US$8 million per year) GEF/WB supporting biodiversity conservation by sponsoring of 100,000 hectares under PES in the priority area of the Costa Rican section of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (among other measures); and social inclusion (increase of participation of women and indigenous communities);

- KfW (German Bank) grant carbon offset project (2000-2007) US$1.8 million per year

€10.2 million over seven years to cover 70 per cent of the state's PES investment in 75,000 hectares in Huetar Norte and Sarapiqui;

- Market instruments

- Reforesta- issue of reforestation bonds: US$5 million (2.6 billion colones) for the first bind issue

- Sale of ES Certificates (CSA-see separate profile): approximately US$1.35 million per year

Analysis of costs and benefits

Economic

Transaction costs are set at sevenper cent of FONAFIFO’S budget (No 32226 MINAE, art 1). According to Rodriguez (2005), FONAFIFO’s total budget over ten years has been 40 billion colones (US$110 million) giving an average annual administration budget of US$770,000.

Participants also incur transaction costs, some paying between 12 and 18 per cent of the total amount of the contract to second tier intermediaries or facilitators which provide help with the application, technical assistance and monitoring. Independent applicants also have extra costs as they have to hire a forest engineer for technical assistance and monitoring .

Opportunity Costs

Returns to land use vary but some of the areas associated with watershed services have high value agricultural and dairy production for export. The payment level is likely to be well below the average per hectare returns from these land uses. A survey of PES participants (Ortiz et al., 2003) found that 67 per cent of those interviewed thought that the PES did not compensate sufficiently for opportunity cost. However, there are also cases where landowners keep land as forest for their own recreational use (second homes) so that returns from other land uses are less relevant.

A study of the highly urban Virilla Watershed (where important water and carbon projects exist) suggested high opportunity costs in areas close to other alternatives need higher incentives to participate (Miranda et al., 2003). Costa Rica is moving from agrarian society towards industry and urbanisation, which creates a different angle in the estimation of opportunity costs of land (Hope et al., 2005, Daniels et al., 2010) where many pressing environmental problems are wastewaters from urban areas, rather than sediments from bad land use, and urbanisation is increasingly one of the biggest threats to ES (Porras and Bruijnzeel, 2006). Higher opportunity costs entail higher risk of deforestation, which suggest higher effectiveness if targeted (Robalino et al., 2008). Increasingly, land in rural areas (especially close to coastal areas) is being bought by foreigners either for tourism purposes or as residential farms. Although there is no study on “who owns Costa Rica,” the trend of exorbitant land prices can drive the competitiveness of the PES out and other measures to prevent conversion may be required (stricter building permits, etc).

Cost effectiveness:

Arriagada (2010) found that during the study period, FONAFIFO paid farmers approximately US$43 per hectare per year under PES contract (increased to ~US$62 per hectare in 2006). Ignoring administrative costs (estimated at about five per cent of total payment budget; Ferraro and Kiss, 2002) and assuming that the treatment effect on forest cover was realised immediately upon contracting and sustained for the eight contracting years, Arriagada generates a lower bound estimate of PES cost-effectiveness (US dollar per hectare gained per year over the study period). His estimate of 8.5 – 12.7 hectares of additional forest cover per farm for payments on about 75.5 hectares of forest per farm implies that Costa Ricans (and donors) paid approximately US$255 to US$382 annually per hectare of additional forest induced by the PES. The cost per hectare in earlier years could be higher if cumulative net gain in forest area over the study period were incremental (e.g., a couple of hectares per year), or lower if the gains in early years were larger than the net gain observed at the end of the study period.

Benefits

The programme has made payments to more than 4,400 farmers and forest owners over the first five years.

The most important economic benefits are the steady cash payments throughout the duration of the contract and in the case of reforestation projects, the expectation of future payments in the form of timber. Many private reserves benefit from PES and use them to set up tourism activities. Being part of the PES also helps with protection from squatters, an important benefit for forest landowners who fear land invasions.

Some forest plantations receiving PES also obtain FSC certification opening up the possibility of a price premium on timber sales, or at least access to specialised certified timber markets. Whether they receive a significant premium or not is not clear.

Environmental

Forest-water link: Pagiola (no date, see below) suggests that at the time when the PES was established there was not enough information available about the links between forest and water. Although the majority of the literature reviewed around the world shows that forests tend to reduce water flows (with uncertainty about dry season flows), this seems to have been ignored when justifying some of the initiatives. For example, a study by CT Energia (2000) analyses six watersheds and concludes that there is a positive relation between forest cover and water flows. Those results have been challenged on the grounds there was not enough data (very few observations per watershed), there was no control data, and at least two of the watersheds showed a negative relation between forest cover and water flows. . Nevertheless, the study was used as the basis for a formula to estimate the benefits from reforestation for hydroelectric projects (estimated between US$6 andUS$50 per hectare per year, with an average of US$20).

Another study by CRESEE (in 2001) concludes that forest cover increases water flows and quality. However, this study only looks at runoff, without examining other key hydrologic variables like evapotranspiration. Despite these limitations, the study was used to justify the ESPH environmentally-adjusted water fee (see separate case profile on ESPH). However, personal communications with representatives from FONAFIFO (Edgar Ortiz, 2005) indicate that in the light of recent hydrological evidence, FONAFIFO is not promoting the "increase in water flows" principle, but rather suggesting the Forestry Law indicate that the protection of forests protects water resources and does not imply that water resources are increased.

Notwithstanding the questions between forest and water flows, several studies pointed out the need to protect important recharge areas from changes to other (potentially more harmful) land uses. In the case of cloud forests, for example, they cover about 12 per cent of the country, and although their marginal impact on water may not be as high as previously thought, attention should focus on protecting forests located on slopes with higher humidity and wind exposure as this contributes more to fog deposition (results from FIESTA study in Monteverde: see policy brief and various technical reports [Porras and Bruijnzeel, 2006]).

PES additionality for “avoided deforestation” requires reconsidering design and implementation explicitly toward that end through improved targeting, which should include metrics for overall landscape connectivity and promote a landscape-level ES provision moving away from the exclusive focus on forests in tropical latitudes (Daniels et al., 2010).

The use of prohibitions and payments: Several studies point out that the law prohibiting deforestation literally means that PES cannot have an impact on reduced deforestation (Sánchez-Azofeifa et al., 2007, Pfaff et al., 2008), but the payment may have helped to make the ban acceptable. Additionality of the programme is therefore questioned on confounding grounds. Interviews of participants in the Virilla area by Miranda et al. (2003) suggest that forest would have been preserved anyway regardless of the payment, but these statements are tarnished by omissions by fear of breaking the law (i.e. landowners would not admit that they intend to break the law).

PES more effective addressing conservation for low-dependent use: Morse et al. (2009) suggest that the effectiveness increases if the emphasis is conservation of existing forest. Using Landsat images, they conclude that the PES programme can be effective in retaining natural forest and recruiting tree cover within biological corridors (study in the Northern area in the San Juan-La Selva Biological Corridor, focusing on farmers with low dependency on forests). A. Daniels (2010) concludes that in Costa Rica the PES is more of an instrument to prevent the loss of standing forest than a forest recovery tool (Daniels et al., 2010).

Impact on reforestation and regeneration very low: Partly because of decreasing deforestation rates, and possibly (but not necessarily) because of the ban on deforestation, the PES has had very low impact for five-year forest-protection contracts originated in 1997, 1998 and 1999, with first-come-first-served approach, which prevented deforestation in their first contract years on only 0.21 per cent of the land enrolled, at most (Pfaff et al., 2008, Robalino et al., 2008).

Later studies found that PES is not totally ineffective (which is different to ‘highly successful’) in increasing forest cover. Arriagada (2010) found in Northern area/Sarapiqui that PES increased participating farm forest cover over an eight-year period by about 11 per cent to 17 per cent of the mean contracted forest area.

Reforestation and restoration are important focus areas for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation

and Forest Degradation (REDD). Although declining, deforestation still continues, mostly in areas of early regeneration; a target for FONAFIFO should be at least 256 thousand hectares per year by 2030 (Saenz Faerrón et al., 2010).

Social

Participation of the Poor. A study aboutpoverty impacts of the PES in Costa Rica (Ortiz et al, 2003) suggests that although the objectives of the Forestry Law initially declared that PES should be a way to strengthen livelihoods in rural areas, the actual PES programme (especially protection) was not initially designed with a poverty-alleviation angle. Using focus groups and interviews, the study finds that most of the participants are relatively well off, and only 15 per cent of them could fall below the poverty line. This is based on criteria such as use of family labour, dependence on agriculture for their livelihoods, declared profession as farmers, use of PES for family expenditure, residence on the farm, size of landholding less than 30 hectares. However, this description puts them more into the "campesino" class and not necessarily poor.

One of the reasons for this lack of participation of poorer farmers is because most of the contracts, until 2002, had been allocated in areas with a SDI of 40-70 per cent. The authors suggested targeting areas with low SDI and this was subsequently introduced as a criterion in the determination of priority areas.

A study by Zbinden and Lee (2004) shows that on average, farms with PES are larger and dedicated to labour-extensive and land-intensive agricultural activities, compared to non-participants. This is confirmed by other studies, showing that larger properties are more likely to enter the PES, excluding small properties (Hope, Porras and Miranda, 2005). Zbinden and Lee say that on average participants in the PES are better educated, more likely to be urban-dwellers, had more income from (and were proportionally more reliant on) off-farm sources and enjoyed higher farm incomes than non-participants

Mortgages and debt. There are some limitations to properties with mortgages. The only ones accepted are for conservation and the payment is made at the end of each year. This might restrict the participation of poorer groups who depend on bank loans for their activities. FONAFIFO has entered into some contracts with the National Bank and IDA that help overcome the restriction of properties with mortgage. On the other hand, a study by Zbinden and Lee (2004) shows that landowners with farm debts consider the guaranteed payments over the five-year contract as an important variable in their decision to participate.

Employment. Ortiz et al. (2003) find that PES conservation projects are mostly neutral in terms of generation of new jobs, especially if compared to other economic activities in marginal areas, but this is less true if the PES takes place in areas with agriculture potential.

The authors suggest that this could be happening in about 23 per cent of the PES protection area. The programme had processed, till the end of 2002, almost US$5.3 million per year, covering approximately 242,000 hectares, over 80 per cent for conservation. A large percentage of this money was used in the farms and 80 per cent reported hiring labour to fulfill obligations for protection.

Encouragement of smallholders.

Information barriers. Zbinden and Lee (2004) show that providing information through meetings and technical advice has a significant impact when encouraging landowners to participate in the PES. Intermediaries and forest professionals should actively seek and advise potential forest owners who they think are likely to qualify. The lack of such advice is likely to result in less participation, as in the case of the Monteverde area, where small and medium scale farmers do not access PES because they do not have enough information about it (Porras and Miranda, 2005).

(i) PES funds the maintenance and improvement of farms, forests and plantations and consequently increases income and enhances quality of life. ii) The scheme can also clarify property rights and protect rural properties against squatters. (iii) PES also leads to the development of knowledge and institutional capacity building and iv) empowerment of grass-roots organizations and NGOs, which have supported the participation of groups that, due to the requirements, individually would be excluded from the programme;

Limitations from application requirements: i) applicants have to submit proof that they do not owe anything to the National Health System (CCSS) and proof that they have not received land from the IDA. This has meant that many small and poor landowners were excluded from PES system. This is a strange limitation since it is difficult to see what the link is between ES and debts with the Health Service, but government regulations forbid people from receiving state funds (which the PES are) if they are debtors to the state in other ways. ii) There is a minimum size required for the plots submitted to the programme (one or two hectares depending on the modality).

A study by Porras (2010) highlights that although FONAFIFO is moving in the right direction and increasing its impact on the poor, it needs to do more to be able to claim to have a genuine social impact. Transaction costs are multiple and expensive, and many of the requirements are fixed costs that weigh more heavily on small properties. Attempts to reduce the entry costs for small farmers have not been entirely successful, and most small farmers still face significant barriers to entry. The experience of group contracts highlights the problem of local intermediation and the heterogeneity of the groups concerned, while using the SDI as a priority criterion has mostly benefited relatively wealthy landowners and companies. Furthermore, given the decreasing levels of the SDI across the country (showing rising levels of poverty throughout), FONAFIFO might be better off to cease using the SDI as the main criterion for eligibility and make more effort to reach poorer farmers directly.

Issues that affect the poor’s ability to participate in the programme:

- Clashes with other state benefits. Early studies by Miranda et al. (2003) point out that poorer households were excluded because of a restriction of not enjoying other state benefits like housing, having land under the Agrarian Land Reform (IDA farms); having mortgages with banks; risk of having to return all payments received if the contract is forfeit. Miranda et al. (2003) report that participants must return all payments received if they forfeit the contract (check what is the state of this now).

- Property titles. Poor land titling problematic in areas where traditionally land is divided among children but not registered (i.e. Monteverde, see Hope et al, 2005). Until land rights and land titles are secured, it is difficult to envisage a more inclusive and ‘pro-poor’ uptake of PES policies in Costa Rica. It also represents problems with lands where IDA has not legally transferred titles to indigenous groups ADIs (CoopeSoliDar RL, no date).

- Reforestation should be allowed in indigenous reserves (CoopeSoliDar RL, no date).

- Ability to enter and manage contracts. Allocation of funds to community groups (indigenous) is sometimes not transparent and ADIs lack management ability (CoopeSoliDar RL, no date)

- Access to information. Poor dissemination of information in remote areas result in farmers not applying because of lack of understanding of programme (i.e. fear of expropriations because of local history, etc.). (Hope et al., 2005) (analysis in Monteverde in 2004 – since then FONAFIFO opened a local office), or not understanding properly their obligations to the contract (Miranda et al., 2003)

- Transaction costs are multiple and difficult for farmers, and waiting times too long and costly (Miranda et al., 2003). Zbiden and Lee’s 2005 econometric model highlights the impact of fixed costs in deterring small farmers from entering PES. The need to reduce superfluous requirements and changing bureaucratic proceedings especially for farmers living away from offices (Porras and Bruijnzeel, 2006). Removing obstacles to participation can help some poorer landowners actually become more competitive service providers (Wünscher et al., 2008)

Legislation Issues

ES were explicitly recognised by the Forestry Law Number 7575, introduced in 1996. The law lays the groundwork for the design of a new national strategy that became the PES or Programa de Pago por Servicios Ambientales (PSA) Programme. The law suggests the use of "polluter pays" and "beneficiary pays" principles in forestry strategy. The services recognised are: carbon sequestration, protection of watersheds, biodiversity conservation, and the provision of scenic beauty. Each year a decree is issued setting up priorities for approving projects. While this might lead to confusion, it also allows for flexibility in the implementation of the projects and for learning-by-doing.

One challenge facing the PES is that the payment levels cannot compete with high return land uses, such as urban developments, in areas that are highly strategic for water recharge. A new law proposal has been drawn up to prohibit any land use apart from forest conservation on land declared as water recharge areas. The proposal would limit agriculture, ranching, urban development, landfills, greenhouses and petrol stations. While this might be extreme, it could lead towards a zoning system.

PES contract is attached to the land, so if the land is sold, the PES goes with it; although the negotiation may be made in a group, contracts are always signed individually.

New water charge law (Canon del agua): The origin of this law (approved in 2006) can be traced to the voluntary agreements with large scale water users. When FONAFIFO came to agreements with these companies on the level of their contribution this gave the MINAE an indication of the Willingness To Pay (WTP) for maintaining regular supply of water. Until now water rates were very low: irrigation US$25 per year, brewery US$400 per year. The new Water Law aims to increase charges for all water users (surface and ground) by nearly 300 per cent phased over a seven-year period. These new charges will be proportional to the amount of water used (consumptive and non-consumptive uses will be charged the same) but different according to the type of user. These changes have encountered strong opposition and FONAFIFO has had to invest in conflict resolution measures; still, the increase now proposed is lower than originally proposed and below the WTP for water for most users. A share of this new water use charge has been earmarked for investments in watershed protection to be allocated in proportion to the revenues generated from the charge in each watershed. Users that are already investing in watershed protection will be exempt from this part of the new charge, as is the case of the ESPH (see case profile).

Monitoring

Monitoring is done by FONAFIFO's regional offices, forest engineers (regentes forestales), or as a joint task between FONAFIFO and the facilitators, where these are involved. State-of-the-art technology has been devised for FONAFIFO using GIS tools and satellite photography to keep track of changes in land use. Breaching contract is reported in only approximately two per cent of cases. Penalties include cessation of payments, and return of payments already made. In cases of serious breach of contract, FONAFIFO brings in the judicial system.

Main Constraints

Flexibility in the programme is a strength, but also a limitation as it generates uncertainty about the rules of the game. For example, pressure from environmental groups led to the termination of the sustainable forest management modality. These groups are now applying pressure to ensure funds for reforestation are available only for projects involving native species. Another problem has been lack of access for properties with mortgages, but recent agreements with some banks are helping to overcome this. Farmers that have received land from the IDA have to approach IDA first and get their permission to apply for PES (land given by IDA is supposed to be for agriculture uses). Funds initially pledged by the state (five per cent of the Fuel Tax) have been cut and reduced to 3.5 per cent. Political support depends on each government and although the programme is relatively solid and strong at the moment, there is uncertainty each time a new government is elected. The programme is trying hard to reduce its dependency on national (and international) funds by diversifying towards other private funds, but most of its income still depends on the Fuel Tax funding.

FONAFIFO identifies as limitations:

i) legal requirements that hinder the access of some land users to the programme;

ii) lack of endorsement from some higher authorities, especially institutions that are important users of ES (this will probably be affected by the new canon del agua which will force every water user to pay);

iii) lack of adequate accounting to include the contribution of the PES and the forestry sector in general, into the GDP (Fonafifo, 2006).

Main policy lessons

The importance of a flexible design – The PES evolves quickly and is good at learning-by-doing. The PES was bound to make many mistakes along the way as no other experiences existed before that could guide it. However, the programme shows high flexibility and a willing team working with FONAFIFO that tries to combine demands at policy level with practical work at field level.

Information is crucial to broadening participation. Providing information and technical advice increases participation in the PES. Active intermediaries could locate potential candidates, but also help smaller ones overcome the barriers to participation. Establishing, managing and following PES contracts is difficult and this tends to exclude the less educated, and often poor, farmers.

The need for clear linkages between forests and hydrological effects , especially for reforestation projects. While most of the current initiatives are based either on perceptions of a positive relation, or rely on improved public relations, the lack of clarity in the linkages prevents expanding the scheme to cover other potential hydrological service users.

It is important to consider the trade-offs between environmental, economic, and social objectives. Although the Forestry Law initially formulated outreach objectives for small and medium scale farmers and provision of income and employment in rural areas, the benefits tend to be enjoyed by the relatively better-off. However, equity objectives like these could conflict with environmental objectives, as larger areas might work better for conservation than small, possibly segregated, plots (Zbinden and Lee, 2004). Administrative costs are also lower when there are few and relatively larger scale participants, whose main source of income is off-farm and who might have less interest in converting the land. However, the reverse can also true; it might be the smaller properties that are most at risk of changing their forest to other land uses and should therefore be targeted.

Because the trade-offs are bound to change from location to location, having active facilitators on the ground might help identify the groups that have more impacts on the ES. This will help to increase efficiency and potentially reduce transaction costs. FONAFIFO could set aside part of its funds to specifically target those groups and give additional incentive to facilitators for this purpose.

The need for systematic spatial targeting to improve efficiency in environmental service provision (See Wunder, 2005, and Pagiola, 2002); "the number of forest owners who apply for enrollment of areas in the scheme far exceeds the availability of funds. This is probably due to a combination of under-funding of the scheme and its lack of systematic spatial targeting. In many cases, those receiving PES funds may not have had genuine intentions in the first place of putting the land to an alternative use, thus implying limited additionality of the system, i.e. the PES system buys less extra environmental protection than would have been possible with increased targeting."

Contact

In FONAFIFO: Edgar Ortiz, Alexandra Saenz.

References

Arriagada, R. A., P. Ferraro, E. Sills, S. Pattanayak, and S. Cordero. 2010. Do payments for environmental services reduce deforestation? A farm level evaluation from Costa Rica.

Barton, D., D. P. Faith, G. Rusch, M. Acevedo, and M. Castro. 2009. Environmental service payments: Evaluating biodiversity conservation trade-offs and cost-efficiency in the Osa Conservation Area, Costa Rica. Journal of Environmental Management 90:901-911.

Blackman, A. and R. T. Woodward. 2010. User financing in a national payments for environmental services programme: Costa Rican hydropower. Ecological Economics 69:1626-1638.

Camacho, M. A., V. Reyes, M. Miranda, and O. Segura. 2003. Gestión local y participación en torno al pago por servicios ambientales: estudios de caso en Costa Rica. UNA, PRISMA, Heredia.

Canales, E. 2006. Cuencas y Ciudades II, un proyecto de recaudacion voluntaria. Zona sujeta a conservacion ecologica, Sierra de Zapaliname, Coahuila, Mexico. International Workshop for Ecosystem Services: Products and Market Development. Forest Trends/Katoomba group and the Sierra Gorda Ecological Group, San Juan del Rio, Querétaro. Mexico.

CoopeSoliDar RL. no date. Memoria de evento.in Participación de los pueblos indígenas en el Programa de Pagos por Servicios Ambientales del Area de Conservación Osa: un acercamiento entre dos culturas, Costa Rica.

Daniels, A., K. Bagstad, V. Esposito, A. Moulaert, and C. M. Rodríguez. 2010. Understanding the impacts of Costa Rica's PES: Are we asking the right questions? Ecological Economics 69:2116-2126.

Ferraro, P. and A. Kiss. 2002. Direct payments to conserve biodiversity. Science 298.

Hartshorn, G., P. Ferraro, and B. Spergel. 2005. Evaluation of the World Bank- GEF Ecomarkets Project in Costa Rica. North Carolina State University.

Hope, R., I. Porras, and M. Miranda. 2005. Can Payments for Environmental Services contribute to poverty reduction? a livelihoods analysis from Arenal, Costa Rica. Centre for Land Use and Water Resources Research.

Miranda, M., I. Porras, and M. L. Moreno. 2003. The social impacts of payments for environmental services in Costa Rica. A quantitative field survey and analysis of the Virilla watershed. . International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Morse, W. C., J. L. Schedlbauer, S. E. Sesnie, B. Finegan, C. A. Harvey, S. J. Hollenhorst, K. L. Kavanagh, D. Stoian, and J. D. Wulfhorst. 2009. Consequences of environmental service payments for forest retention and recruitment in a Costa Rican biological corridor. Ecology and Society 14:23[online].

Ortiz, E., L. F. Sage, and C. Borge. 2003. Impacto del Programa de Pago por Servicios Ambientales en Costa Rica como medio de reducción de la pobreza en los medios rurales. RUTA, San José.

Pagiola, S., P. Agostini, J. Gobbi, C. De Haan, M. Ibrahim, E. Murgueitio, E. Ramírez, M. Rosales, and J. P. Ruiz. 2004. Paying for biodiversity conservation services in agricultural landscapes. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Pagiola, S., A. Rios, and A. Arcenas. 2007. Poor household participation in payments for environmental services: lessons from the Silvopastoral Project in Quindío, Colombia. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Pfaff, A., S. Kerr, L. Lipper, R. Cavatassi, B. Davis, J. Hendy, and A. Sanchez-Azofeifa. 2007. Will buying tropical forest carbon benefit the poor? Evidence from Costa Rica. Land use Policy 24:600-610.

Pfaff, A., J. Robalino, and G. A. Sánchez-Azofeifa. 2008. Payments for Environmental Services: Empirical analysis for Costa Rica. Working Papers Series Terry Stanford Institute of Public Policy Duke.

Porras, I. 2008. Forests, flows and markets for watershed environmental services: evidence from Costa Rica and Panama. University Of Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK.

Porras, I. 2010. Green and fair? The social impacts of payments for environmental services in Costa Rica. International Institute for Environment and Development, London, UK.

Porras, I. and L. A. Bruijnzeel. 2006. Cloud forests: water, livelihoods and payments for environmental services in Costa Rica. CLUWRR, Viejre Universitiet, IIED, Cinpe Costa Rica, Kings College London, TEC Costa Rica, FRP-DFID.

Robalino, J., A. Pffaf, A. Sánchez-Azofeifa, F. Alpízar, C. León, and C. M. Rodríguez. 2008. Deforestation impacts of environmental services payments. Costa Rica’s PSA Programme 2000-2005. Environment for Development Discussion Paper Series, August 2008 EfD DP 08-24.

Rojas, M. and B. Aylward. 2003. What are we learning from experiences with markets for environmental services in Costa Rica? A review and critique of the literature. International Institute for Environment and Development.

Saenz Faerrón, A., J. M. Rodríguez Zúñiga, M. E. Herrera, E. Ortiz Malavassi, C. Borge, and G. Obando. 2010. Propuesta para la preparación de Readiness R-PP Costa Rica. Gobierno de Costa Rica.

Sánchez-Azofeifa, A., A. Pfaff, J. Robalino, and J. Boomhower. 2007. Costa Rica’s Payment for Environmental Services Programme: intention, implementation, and impact. Conservation Biology 21:1165-1173.

Sierra, R. and E. Russman. 2006. On the efficiency of environmental service payments: A forest conservation assessment in the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. Ecological Economics 59:131-141.

Watson, V., S. Cervantes, C. Castro, L. Mora, M. Solis, I. Porras, and B. Conejo. 1998. Making space for better forestry: Costa Rica. Tropical Science Centre, JUNAFORCA, International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

World Bank. 2000. Ecomarkets Project: Project Appraisal Document. World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2006. Scaling up and mainstreaming payment for environmental services in Costa Rica. Project Appraisal. . The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Wünscher, T., S. Engel, and S. Wunder. 2008. Spatial targeting of payments for environmental services: A tool for boosting conservation benefits. Ecological Economics 65:822-833.

Zbinden, S. and D. Lee. 2005. Paying for Environmental Services: An Analysis of Participation in Costa Rica’s PSA Programme. World Development 33:17.

Links

FONAFIFO website: www.fonafifo.com (some pages available in English)

Requisites to participate in the PES programme: http://www.fonafifo.com/paginas_english/environmental_services/sa_requisitos.htm

Statistics on land under PES and contracts: http://www.fonafifo.com/paginas_espanol/servicios_ambientales/sa_estadisticas.htm

Pagiola (no date): www.ine.gob.mx/ueajei/publicaciones/libros/423/cap3.html

|

|

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top

back to top |