International Institute for Environment and Development

80-86 Gray's Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH

info@iied.org

www.iied.org

tel: +44 (0)20 3463 7399

fax: +44 (0)20 3514 9055

Case Studies:

NGO MYRADA’s watershed management work in Kartanaka state MYRADA manages watersheds or micro-watersheds and Participatory and Integrated Development of Watersheds (PIDOW). In 2005 MYRADA treated over 126,000 hectares. As the buyers and sellers of Environmental Services (ES) are not clearly distinguishable from each other, this case is not strictly a payment scheme and is closer to a community development project. It is therefore considered a borderline case.

Watershed management initiatives have been going on since 1985, some of which are still active as of 2008.

MYRADA has played a key role in building up financing schemes, but ultimately the payments are driven by a realisation that watershed management has direct effects on farmers’ livelihoods.

SupplyPrivate individuals within the catchment at Gulbarga, Karnataka, who are contracted by self-help groups to regenerate and maintain fallow in upland areas (private and common land) or who are given loans to implement measures on their own land. Although the scheme is site-specific, in some cases participants are both “providers of the service”, by implementing watershed management activities, and “users of the service,” as members of the self-help cooperative groups.

DemandSelf-help groups implement the watershed development plans by contracting local farmers to regenerate and maintain fallow land in upland areas. The self-help group also lends money (often interest free) to farmers who wish to implement their own measures on their land. Villagers taking the loans to invest in watershed management donate labour for improvements. Contributions reflect the expected benefit that farmers will gain. Farmers place higher value on activities that will provide immediate returns, e.g. silt traps. Government or NGOs also provide grants.

IntermediaryMYRADA and Self-help Affinity Groups (SAGs).

FacilitatorsMYRADA (NGO), international groups and donors such as the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID), the World Bank, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), women development corporations, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the government, the Asian Development Bank and the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). ServiceWater quality and flow regulation.

CommodityImproved management practices: through participatory integrated watershed management projects, especially in rain-fed agricultural areas. Water harvesting and soil and water conservation techniques on farmland: field bunding (bunds are micro-catchments with trenches dug on the inside of the plot, earthen mounds on the outside, to hold soil and water), vermin-composting and silt application.

Payment MechanismCommunity Based Organisation (CBO) intermediaries & pooled transaction - payments to upland farmers and landless made through self-help groups who pay either directly (contracts) or indirectly through cheap loans to undertake watershed protection activities. Groups supported by an NGO, MYRADA. In 1993, 103 self-help groups established, each of which manages a fund. Management of funds: In most cases, the self-help group receives a grant through a government scheme or an NGO. The group converts this into loans for treatment on private lands. Each group chooses their interest rates. Some loans are interest-free, others have rates ranging from 5-15 per cent per annum, but all treatment measures on common lands are supported through grants and in-kind contributions of labour. . The Myrada project reports from 32 microwatershed reports that loans (rather than contributions) improve motivation to better monitoring and managing of investments (Prakash Fernandez, 2003).

Terms of PaymentCash and in-kind (depending on expected benefit). Cash payments (one-offs) to landowners in the form of contracts or cheap credit.

Loans or paymentsMYRADA has tried different types of contributions. In 1984 it tried in-kind contributions in the form of labour, but found it impossible to put a price on the value of this labour for the auditors and evaluators of the project. It tried cash contributions in the early 1990s, but the problems were: a) people do not place the same value on different structures and therefore the contributions differed; and b) people found it difficult to raise contributions in cash upfront, particularly when these coincided with periods of high household expenditures. The solution they adopted was to borrow money from the SAGs, of which people were members.

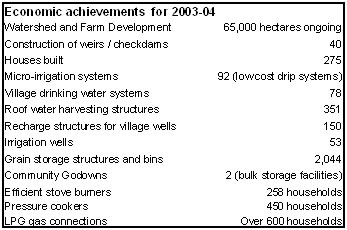

Funds InvolvedAccording to MYRADA: “Between April 2003 and March 2004, the 8,411 self-help groups in our project areas mobilised Rs.117,369,850/- directly from banks under the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme. The addition to their Common Fund during the year (through members' savings, service charges on loans advanced, fines, donations, etc.) was to the order of Rs.210,586,106/-. The money in their control was used to give 140,938 loans to members during the year” (MYRADA website: http://www.myrada.org/achievements.htm). Beginning in 2008 continuing through 2009, approximately US$50.8 million collectively moved through the multiple Myrada programs (data on a per watershed basis was unavailable). Analysis of costs and benefits EconomicMedium/high level of competition - water beneficiary self-help groups need to pay upland landholders and users a competitive incentive to participate in watershed management. When the loan element was introduced, the cost of structures came down – monitoring of implementation improved and diversification in the cropping pattern (including the introduction of cash crops) increased. MYRADA still does not know if the loans will have an effect on watershed management after the project finishes. People do not see loans in the same way they see contributions – farmers are more interested in improved monitoring through loans. Contributions are seen as a necessary condition to receive a benefit, rather than as an investment that needs to be carefully managed. The amount of money required for land treatment under rain-fed agriculture is far more then what is available in grants. Grants do not normally cover maintenance of structure, which tends to be covered through repayments held by watershed institutions.

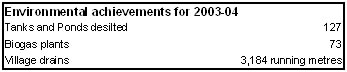

EnvironmentalMYRADA’s experience shows that unless people feel a direct link between efforts and investment to manage water flows (protecting and regenerating upper reaches, treating nalas and private agricultural lands lying fallow) and increases in agricultural and biomass productivity, there is no motivation for sustained management of treatment measures on degraded areas.

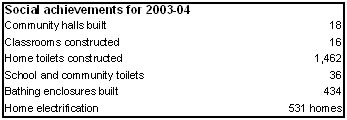

Social“Management of surface water flows can only be done efficiently and effectively as a result of people’s active cooperation”. A key feature of the projects supported by MYRADA is that they promote equality. As a result, there are in-built mechanisms for ensuring the self-help groups provide support to the disadvantaged. Landless people, for instance, are provided with employment in implementing work and help in developing new skills. The landless also have access to cheap credit. Marginal farmers are also given special attention. MYRADA has also produced a large amount of material (such as handbooks etc) on self-help groups, institutions, and watershed management. (see MYRADA website). SAGs comprise approximately 25-30 families, which in MYRADA’s experience is structurally appropriate (being small and with reduced risk of leadership conflict). Larger groups tend to result in marginalisation of the poor. In the CIDOW project in Molkalmoru, for example, the project benefits over 1,700 farmers, of which more than 70 per cent are small and marginal. Cases of Panchayat Raj Institutions (PRIs) – decentralized institutions of representative democracy (rather than participative) show that some of their Steering Committees are more interested in pleasing parties than effective implementation of an integrated watershed programme. While they are important, SAGs can help promote interests of marginalized groups such as women and the poor. They lobby to provide credit for their livelihoods and to ensure that the landless benefit from the investment in natural resources. Significant investment is made in health and sanitation, including training, targeting of vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and children, environmental education, construction of toilets and water connections. The project also invests in local schools.

Institutional monitoring: MYRADA has created a set of guidelines for field workers on how to assess impacts on SAGs and Watershed Management Institutions.

Local action feeding into national policy:MYRADA has tried to incorporate the loan culture into government sponsored schemes without success. The shortage of resources means that programmes are administrated by government staff, excluding the NGOs that possess the skills to promote people’s institutions. Bureaucracies can also cause long delays, for example application for certificates. Watershed programmes are not implemented during the months when people have spare time available, but depend on availability of funds at the state level. This has a negative impact on promoting people’s participation. This initiative is more an example of existing cooperative arrangements and formal support by an NGO, than markets as such. The market evolved alongside the creation of cooperative structures (self-help groups). MYRADA’s experience suggests that loans for treatment on private lands should become a feature in watershed programmes. Loan culture has reduced the cost of structures, improved quality of monitoring in implementation and reduced leakages in the delivery system. There are cases where political party alliances have undermined the formation of committees at a larger scale (500 hectares), but that problem is reduced if there is adequate training and support given to the area groups. MYRADA’s approach of SAGs is being promoted in other countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, East Timor, Eritrea and Sudan. MYRADA has arranged visits of these teams to India to interact with various stakeholders like NGOs, government functionaries, bankers and CBOs.

http://www.myrada.org/contact.htm

MYRADA, Newsletter 4, September 2005. MYRADA website: http://www.myrada.org Prakash, Aloysius. 2003. Watershed Management: Are loans more effective in promoting participation and ownership than contribution? The roles of Panchayat Raj Institutions. MYRADA, Rural Management Systems Series Paper 36.

For more examples of Myrada’s work, see map in http://www.myrada.org/projects.htm |

|

© 2012 International Institute for Environment and Development . All rights reserved.